...No one unwell, or indeed anyone at all, should forgo or otherwise lose the moment and pleasure of reading Thomas Mann's 'The Magic Mountain.'

General readers will delight in the extended exposition on disease (tuberculosis in this case) as a metaphor for some of the finest as well as many of the most wretched aspects of the human condition. Male readers - though not exclusively - ought to find at least a part of them in complete accord with the questing mind and seeking soul of its central character, young Hans Castorp. Tears even might be shed when, after seven years' seclusion in his mountain-top sanatorium, he of a sudden plunges back into the maelstrom of the impending First World War. A serious and a thoughtful seeker after experience, knowledge and even some wisdom, but above all a patriot.

Tears most certainly ought to be shed for his cousin Joachim's brave soldierly defiance of his fatal illness, and for his stubborn refusal, in such exigent circumstances, to bend even one inch of his silly stiff neck to acknowledge and own the raging passion he holds deep in his heart for a lady whom he sees every day over many years, yet to whom he never once addresses a single word because, simply, they have not been formally introduced.

For Hans, illness offers some loosening of the social constraints that bind a young, correct German man of his generation - his famous and fabulous 'Walpurgis Night' - but for Joachim, anything of that sort would be mere sign of weakness in the face of an enemy. They are indeed a fine contrasting pair throughout, even after Joachim's premature, heroic death. But no more on that, if you wish to know how he lives on and with what extraordinary consequences for his cousin Hans then to the book itself you must go.

But if they differ, these two, in their willingness to 'cut loose', both inevitably are drawn by curiosity to explore the very thing that binds them to the Berghof - their pulmonary self and the decay within. Each patient becomes their own expert at the marvellous 'cure': from rug-wrapping against the evening chill on their balconies, to recognising by sound alone the import of each 'tap, tap, tap' as Behrens knocks their torsos exploring for dry scar tissue and wet live disease; from courteous visits to the suffering moribund whose dying is an affront to the regime of the place, to the compassionate acceptance of the hysterics who rail against their lethal misfortune and all decency.

These are, of course, early days for the science of diagnostics by machine. Generations of skill perhaps for telling when a man grows better or sicker by sight and by touch alone, but it is now the very new X-ray apparatus that permits both physician and patient alike to view the live inner flesh at work and, of course, the terrible fell thing within that is flesh of their flesh yet also the harbinger of its total destruction. They will see themselves alive, but will also be a witness to their own dying.

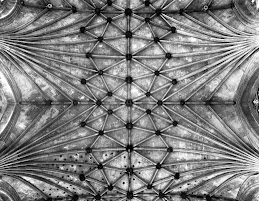

This peep behind the curtain, as it were, of existence itself is a mighty and modern privilege, something to be approached - if at all - with a certain numinous awe as well as perhaps a near religious dread. It can be done, but maybe it is not a thing that ought to be done. This is knowledge intended perhaps not for a man but for his God only.

Doctors, though, respect but are not quailed by these quite proper sentiments. Behrens ushers the cousinly pair into his darkened laboratory, accepting their trepidation - allowing some due ceremonial indeed to the occasion - yet also briskly setting dials, pressing buttons and aligning plates as they strip to the waist in preparation for their ordeal by radiation, standing almost to attention - Joachim fully martial in stance even - waiting the orders of their superior to attend for innermost examination.

Read the text for the humour of the machine itself. Perhaps Mann did not intend it, though I believe he did. No silent running as we moderns are used to, but a great snapping, crackling and popping summonsing of mysterious, semi-demonic radioactive forces. A conjuring almost, a cross between Dr. Frankenstein and the Wizard of Oz.

And behold then the magic of the mountain - a man observes his inner being, his living beating flesh. Hans and Joachim are suitably smitten with the wonder of the thing. One wonder though was not theirs to have, the great question: am I sick or am I well? They were already feverish with their tuberculosis. The picture of themselves they saw was, in the end, but a visual confirmation of pre-existing knowledge. Awesome certainly, but not a revelation of anything other than that they were mortal.

My forthcoming CT scan is so much like theirs and yet so very different. It too will peer deep inside me, show doctors and myself hidden regions and inner workings. I, as the cousins, may well ponder whether this is a sight fit for a man to see. It will, however, be a quiet affair, I shan't know the minute the picture is taken, no smiling for the birdie. Not even, these days, a physical photographic plate to take away with me, one to be feverishly searched for clues by the ignorant patient in advance of the knowing doctor's review.

In the old days I would walk into the appointment with the plates under my arms. My oncologist would be none the wiser at that moment than I. Only when she had taken the plates from me and posted them on her screen would I know that she was finding out what they said. I would keenly watch her face for any trace of revealing thought or emotion. She in her turn would give nothing away until she was ready to speak. A tense few moments as you can imagine.

This time around it will be different. The scans will have been emailed in advance and she - or whoever it is with this new disease - will already have reviewed them, determined her conclusions and be prepared, the moment I am through that door, to give them.

Behrens would never have been saying to the cousins: "My Lord, I have been wrong all these years. You haven't got - never have had - tuberculosis." My man or woman, however may be saying to me: "By crikey, I never expected to find any evidence of spread, but I am so very sorry to say that's precisely it. I have."

Plenty of crackling and popping before that moment arrives, not to mention an inevitable amount of snapping all round. Time then, once more, perhaps to re-read Manns great work on man.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment