You can see at once the tactical flaw. It's one thing, when you are struggling on foot home at night through the freshly-fallen snow beyond your boot tops, to be hailed by two pukka, uniformed, police officers with offers of a warm and safe haven with fresh-made soup attached. "Up at the monastery Sir. Follow the drive to the top of the hill and Father Prior will greet you with a hot mug of finest fresh-made, plus the offer of a bed for the night." Just the thing if you've had to abandon your car in the sudden storm, are miles from home and have nowt but a wailing, scared young family for company.

Quite though another thing altogether, when the very same offer is being made by two anonymous strangers in mufti - with not a badge of officialdom between them - pointing you off the lawful, if impassable, Queen's highway towards a darkened path and an uncertain future.

The night had begun well enough. There we were 'proceeding in a westerly direction' down the nave, having said good night both to the living Lord and to Victor in his coffin, when we were apprehended of a sudden by the aforementioned officers of the law with a proposition that we, in Christian charity, could not reasonably decline.

"Folk are stranded by the shedload, good Fathers. Abandoned cars line the streets, roads and one or two of your hedgerows. You may be holy souls given over to adoration of God alone, but even you unworldly types must have noticed the snow that has pelted down these past hours. We were wondering if we could send some needy folk your way for hot soup and safe sanctuary from the savage storm?"

Put thus, how indeed could there be any refusal? Enormous gaff the monastery, could hold two hundred plus and still leave room for the chickens. Not the normal routine for a contemplative order, strictly enclosed, with an impending funeral on its hands and about to go to bed. But normal in no way were the circs. Three hours previous, a light shower of wet slush. Now though, a wipe-out blizzard and nine inches or more of the white stuff lay all around. Quite on the hop it had taken all it seems.

The sensible ones had parked their cars by the side of the road to consider their options. The more foolish had taken a run at the hill, simply sliding to a halt much like the old Duke of York cove - neither up nor down.

Now, if only dear old Victor had not upped and died he would have been in his element bustling about and around, sorting the logistics; ordering, listing then delegating the tasks, and generally getting to grips with the situation as arisen. His only regret, probably, would have been that the solving of the problem did not necessarily require immediate banging nails into planks of timber in order to build something on the spot. (No doubt, though, he would have taken the blow on the chin and set aside the splendid notion of knocking-up a new twenty-four bed guest wing as something for the morning.)

The soup, of course, was the key note of the thing, much favourably commented on by the temporary refugees. (A little vegetable and tomato number I conjured from the limited ingredients on offer.) That though accomplished, it was someone's bright idea - mine I fear - to relieve the two officers of the law for a short respite from the storm. "Let them warm up a tad, as they've clearly got an all-nighter on their hands, and two of us can go down the bottom of the drive in order to shepherd the lost sheep towards sanctuary.

No sooner said than done. No sooner done than the two freezing police constables were thawing out by the monastery pipes. No sooner, though, than their replacements in place, when passing trade slackens off no end. Made their excuses and fled (to the extent that anyone can flee through heavy snow) about summed up the response to our offer of hospitality. Marty Feldman reprising his 'Young Frankenstein' Igor role would have had more success than we did. "Walk this way." "Why of course." (If you haven't seen the film then you'll not get the reference, but if you've not seen the film you shouldn't be allowed out after dark anyway.)

Realisation rapidly dawning, roles once more reversed, the interrupted flow was resumed. Final score on the door something like: one extensive Eastern European family with minimal English, less luggage and a dazed looking toddler; five or so single adults of both genders, who may or who may have thought that bedding down with the monks was the Christmas present they'd always wanted but never dared ask Santa for; an upright and somewhat puzzled old gentleman who could well have caught his death of cold in his benighted car; a mother with a teenage daughter whose happy demeanour and sparkling good looks may well have given a wobble to a celibate vocation or two, plus a young son - the spitting image of dear Nick Drake - who looked totally terrified when it was jestingly suggested that he was ideal monastery fodder and shouldn't be allowed to leave in the morning; and two terribly humane constables who were destined to freeze their butts off at least 'til dawn and beyond.

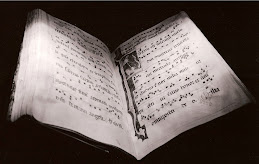

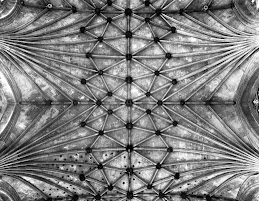

Just two of the monks were caught up in the turmoil, the rest having retired to their rest. But not quite so though, for it is the monastic tradition to keep watch during that night with a deceased brethren who is awaiting his burial the day following. Hour by hour, one monk would replace another to kneel in prayer in the dark - and that night freezing - church beside the coffin. Theirs the more silent, the hidden and the traditional monastic witness than our exigent banging about finding broth and beds for the temporarily stranded.

Martha and Mary, both, we were then in our respective ways. Martha's endeavours will merit a proper, if transient, headline or two in the local press - along with many others who gave aid and succour that bitter night. Mary's witness won't get a mention, except here and in Heaven.

Thursday, January 07, 2010

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)